The NP approach to cancer: the chemotherapy cheat sheet

💬 comments

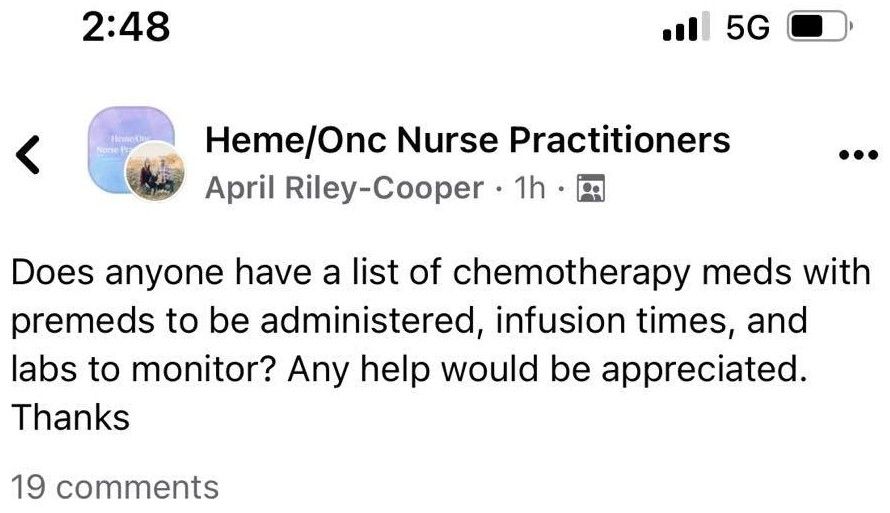

Why spend three years in a hematology-oncology fellowship when you can just become an NP and ask Facebook for a list of chemo meds?

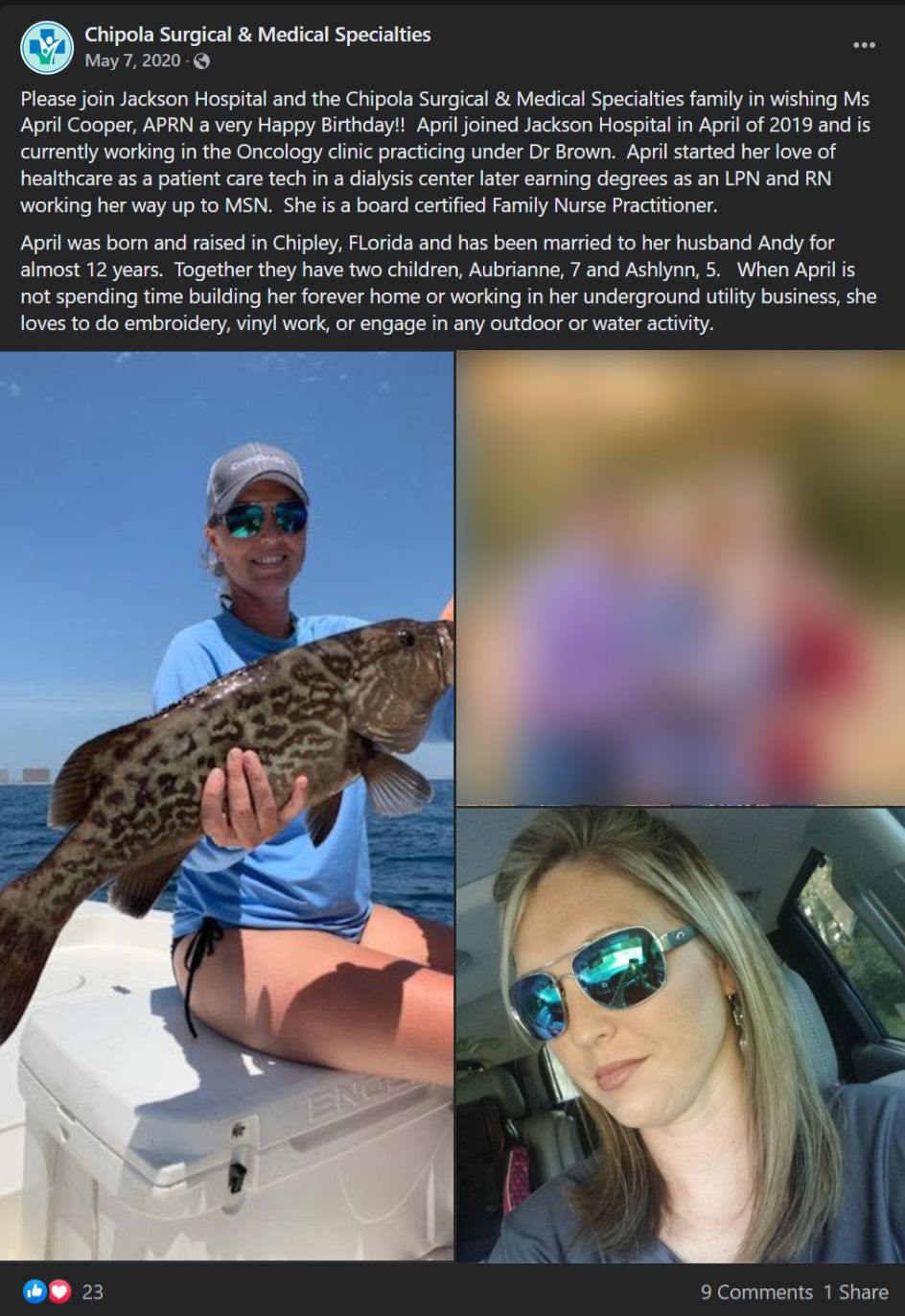

Have you ever seen a board-certified hematologist-oncologist asking for a list of chemotherapy medications? A web developer asking how to make a website? A pilot asking how to fly an airplane? The answer is a resounding no, because presumably, all of the aforementioned professionals had adequate amounts of education and training. Unfortunately for patients, as demonstrated by the Facebook consult above, the same can't be said of nurse practitioners such as April Riley-Cooper.

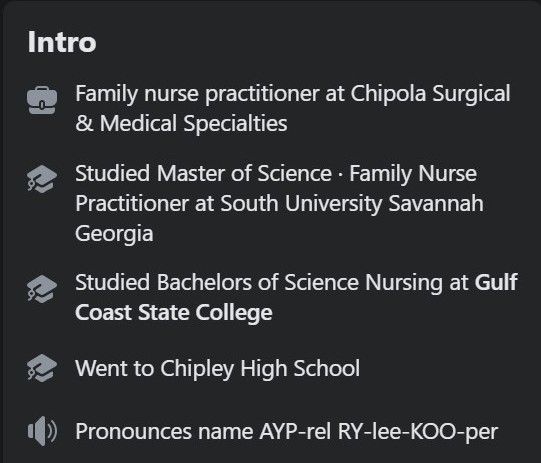

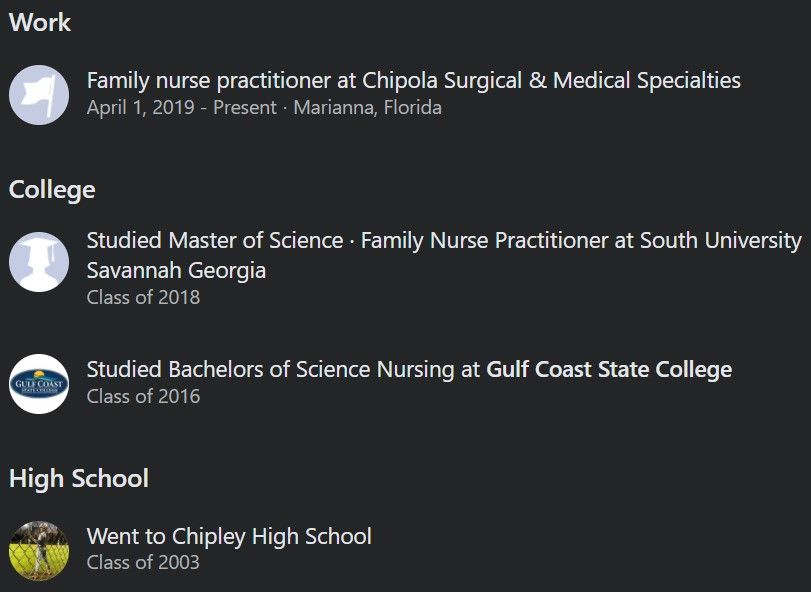

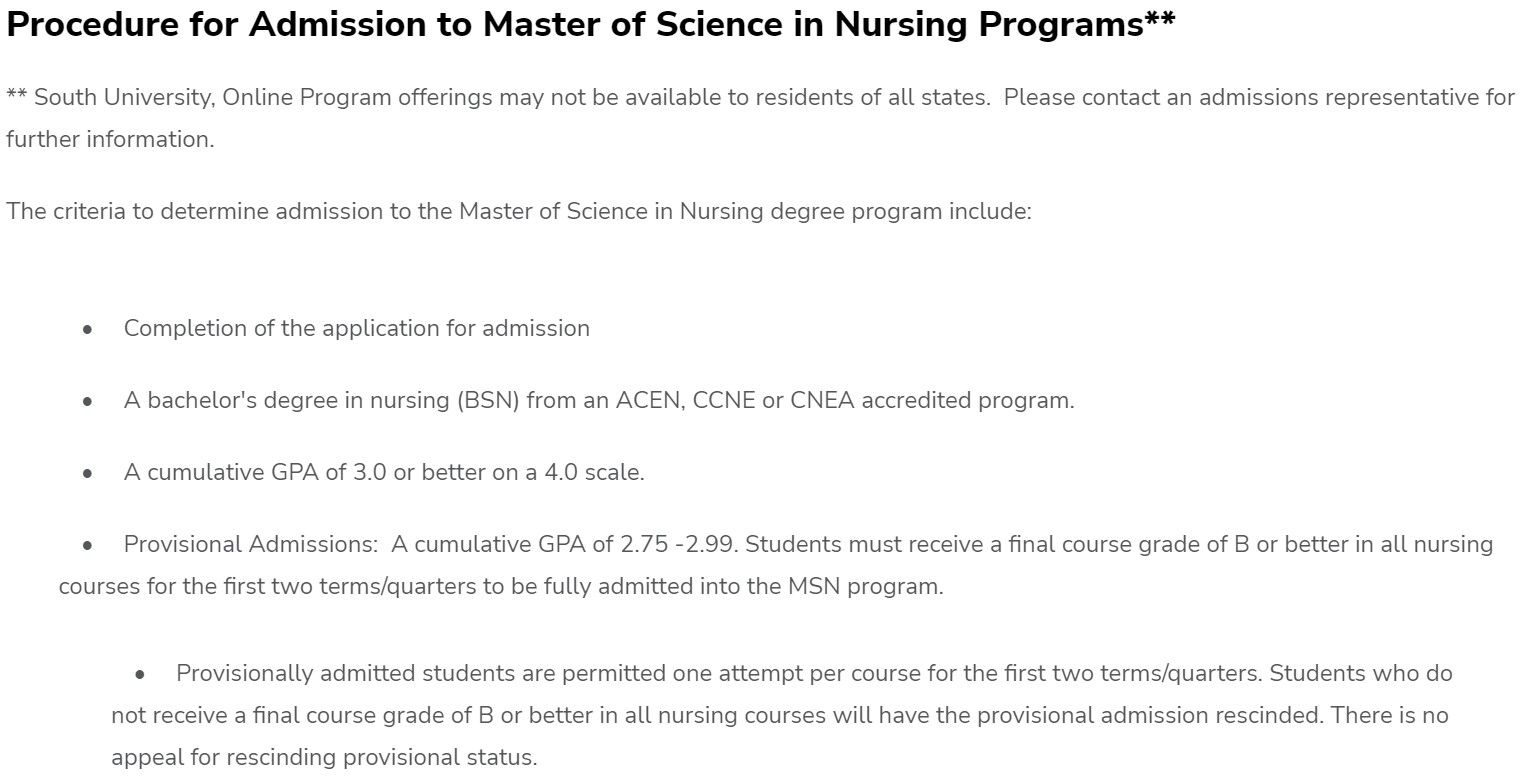

When the educational standard for nurse practitioners these days is to pay for a degree from a 100% online diploma mill and pass off a few hundred hours of glorified shadowing as "clinical experience", followed by direct entry into hospitals and clinics with no postgraduate specialty training whatsoever, it's no wonder how a family nurse practitioner like April Riley-Cooper suddenly ends up working in an oncology clinic only one year after graduation from her MSN-FNP program, begging a Facebook group for a cheat sheet on what should be bread-and-butter core knowledge for someone working in oncology. By contrast, a physician will have needed to complete four years of medical school, three years of internal medicine residency, and another three years in hematology-oncology fellowship before being allowed the privilege of calling themself a medical oncologist. Mind you, getting into a heme/onc fellowship is no walk in the park. As a research-heavy and increasingly competitive specialty, it has become more and more difficult to match into, with only a 73% match rate in 2018. And then there's the preceding difficulty of getting accepted into medical school and matching into a well-regarded academic internal medicine residency program, which is a de facto prerequisite for landing a competitive fellowship. Now, consider pitting all that against the amazingly rigorous (😂) admissions requirements for the South University MSN-FNP program.

Besides the obvious scope-of-practice concerns that arise from an FNP working in oncology (hell, family medicine physicians aren't even allowed to pursue internal medicine fellowships such as hematology-oncology!), it doesn't take a genius to understand the disturbing real-life implications of allowing a midlevel like FNP April Riley-Cooper near vulnerable cancer patients. Physicians do not practice medicine by using cheat sheets provided by Facebook groups. If you suddenly developed a malignancy and required chemotherapy, would you want to place your life in the hands of a bumbling NP who needs to ask the Facebook peanut gallery for a list of not only chemotherapy medications, but how long to infuse them for and what labs to check afterward? Needless to say, the management and treatment of cancer is no trivial manner, and we're saying this as physicians without specialist expertise in oncology. Chemotherapy regimens are usually administered over several cycles and sessions, and quite frankly, having an incompetent midlevel nurse practitioner involved might as well be a death sentence.

While the educational standards (or more precisely, the lack thereof) of nurse practitioners and other midlevels obviously poses a huge problem, the hospitals and clinics that employ these incompetent practitioners are also to blame. Admittedly, the decision to hire midlevels is often due to market forces and financial pressures. Taking into account the shortage of physicians, the difficulty in attracting them (especially specialists like oncologists) to less-than-desirable locations such as the economically depressed Florida Panhandle town of Marianna, and the comparatively low salaries of midlevel providers, it's no wonder why hospitals and health systems - especially small players like Jackson Hospital - to hire questionably qualified midlevel providers, even if it means turning a blind eye to ethics, quality of care, and patient safety.